Three scientists have developed materials so porous that they can trap pollution, harvest water from desert air, and potentially even slow climate change.

Filter toxic chemicals and so-called “forever pollutants” from soil or groundwater

3 Narratives News | October 8, 2025

Intro

A sponge can soak up water.

Now imagine one that can soak up carbon dioxide, toxic gases, or even humidity drawn from desert air.

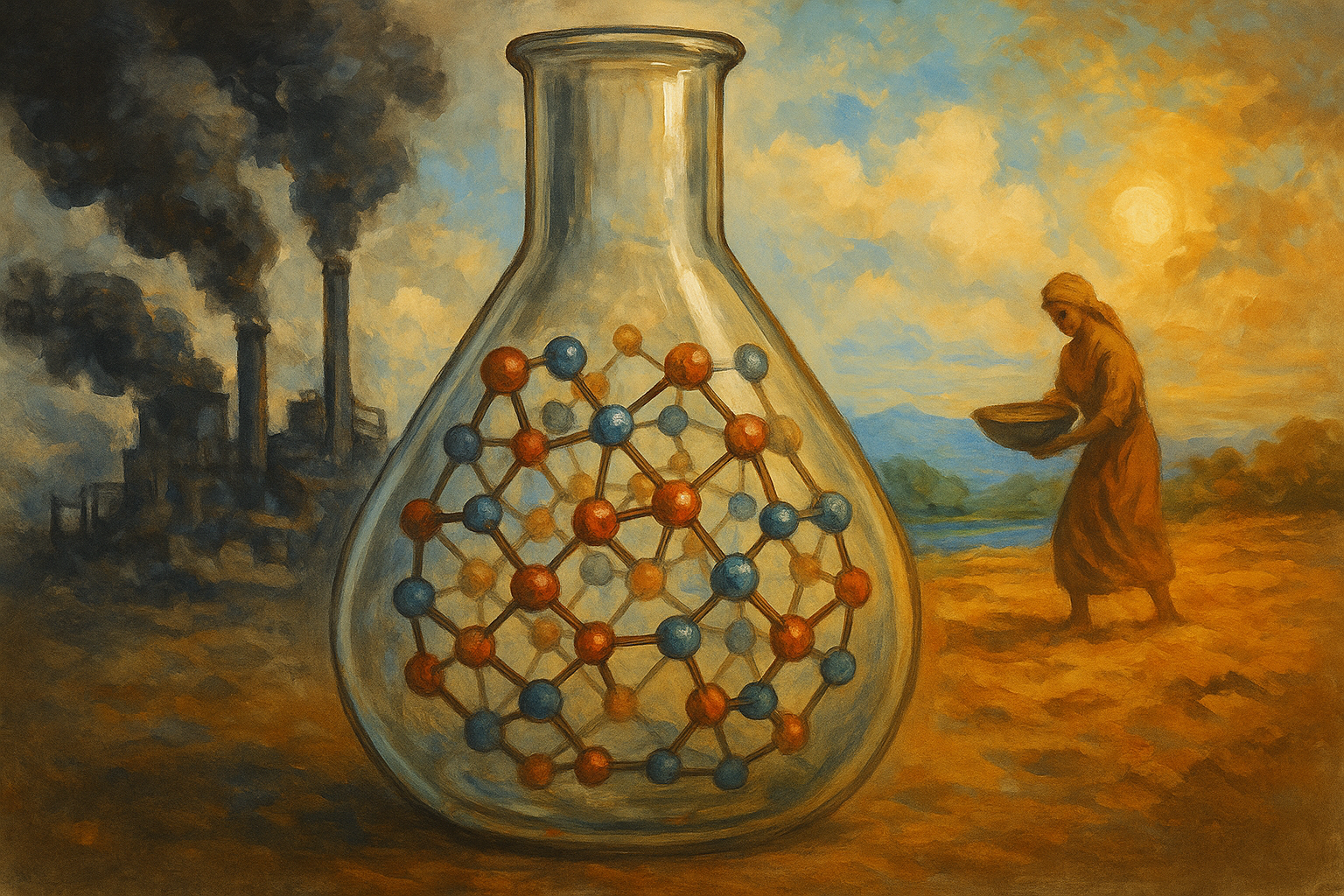

That is what Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi created: materials so full of microscopic holes that a single spoonful has the surface area of a football field.

Today, they were awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for discovering metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs, intricate structures that can trap, store, and release gases or liquids. Their invention could revolutionize the world’s approach to tackling pollution, drought, and climate change.

The Problems We Face

Across the planet, the signs are hard to miss.

Cities choke under smog.

Farmers in Africa and Asia watch wells run dry.

Coastal towns brace for floods, while inland regions face rising heat and dust.

Human progress keeps expanding, yet so does the waste it leaves behind. Cars and factories release carbon dioxide into the air. Farms emit methane. Oceans are filled with invisible plastic. Every solution we invent seems to create a new problem somewhere else.

Even as nations promise green energy transitions, the chemistry of daily life, so how we make fuel, food, fertilizer, and medicine, still depends on burning or polluting processes.

In poorer regions, the crisis takes a different shape. Villages struggle to find clean water. Crops wither under sun-baked skies. Relief trucks bring bottled water that runs out in days.

The challenge, scientists say, isn’t only to invent new technology, but to build materials that can do nature’s work that is faster, cheaper, and anywhere on Earth.

The Solutions Hidden in the Smallest Spaces

That is where this Nobel discovery begins.

The three chemists, Kitagawa from Japan, Robson from Australia, and Yaghi, born in Jordan and now working in the United States, spent decades studying how to link metal atoms with organic molecules. When arranged in precise patterns, these atoms form a repeating crystal network filled with tiny empty chambers.

Those chambers are unimaginably small, yet each can hold or filter a particular gas or liquid.

These materials are called metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs.

Imagine a microscopic hotel for molecules. The walls are strong, but what matters is the open space inside. The more space, the more “guests” it can hold: water vapour, carbon dioxide, methane, or other gases.

Because scientists can design the size and shape of these molecular rooms, they can tailor MOFs for almost any job:

- Capture carbon dioxide from smokestacks or directly from the air

- Store hydrogen or methane for clean, portable fuel

- Harvest water from dry desert air, even overnight

- Filter toxic chemicals and so-called “forever pollutants” from soil or groundwater

- Deliver medicines inside the human body with precision

- Accelerate chemical reactions in cleaner manufacturing processes

Professor Omar Yaghi once compared MOFs to “Lego made of atoms.” Each atomic piece fits with others to build new functions, just as children build castles from blocks.

A growing number of scientists call them “the materials of the century.” Some even compare them to Hermione’s handbag from Harry Potter — small on the outside but infinite within.

The Silent Story

In a century defined by climate anxiety, the story of these molecules feels almost quiet.

The scientists who developed them never promised miracles. They showed instead that even empty space can hold possibility, that the gaps between atoms, when arranged with care, can help mend the gaps we have made in the planet.

Across the world, prototypes are already at work.

In Abu Dhabi, MOF filters pull drinkable water from desert air.

In California, engineers redesign carbon traps in factories using MOF membranes.

In India, small start-ups test air-purifying devices for schools and hospitals.

The technology is still expensive, fragile, and new. But in a world running short on time, it offers something rare, a reason for hope grounded in science.

Someday, these invisible lattices may live inside every purifier, every factory chimney, every drought-stricken field — quietly absorbing what we can no longer afford to ignore.

Key Takeaways

- The 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi for developing metal-organic frameworks (MOFs).

- MOFs are porous materials that can trap, store, or release gases and liquids, like a sponge at the molecular level.

- They could help solve urgent global problems, from carbon emissions to water scarcity and chemical pollution.

- MOFs are already being tested in air filters, water harvesters, and drug delivery systems.

- The discovery reminds us that innovation often begins not with machines, but with the invisible architecture of matter itself.

Questions This Article Answers

1 How can MOFs help fight climate change and pollution? 2 What are metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)? 3 Who won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and why? 4 What real-world problems could this technology solve? 5 Why is this discovery being called “the material of the future”?