By Carlos Taylhardat, 3Narratives

As a boy in Estoril, a quiet seaside town outside Lisbon, my childhood was colored more by incense and ritual than by cartoons or television. In 1970s Portugal—then among the least developed countries in Western Europe—our lives moved slowly, anchored by the rhythms of the Catholic calendar. We had one TV channel, often too fuzzy to watch. But we had something more enduring: the Virgin of Fátima, and the Pope—God’s voice on earth.

At school, we learned arithmetic and writing in the morning, but by afternoon, our lessons turned to catechism. We were taught, quite plainly, that the Pope was the closest living person to God. And I believed it—so much that I once considered becoming a priest. My faith was deep and unquestioning.

It was only after immigrating to Canada that my ideas began to shift. I learned my sixth-grade teacher was Jewish. She was kind, thoughtful, and intelligent—and I remember crying quietly at night, praying that God would not send her to hell simply because of her religion. That year, something opened in me. I started reading about Judaism, then Buddhism, then Hinduism. I discovered a world full of other truths, other prayers, other ways of being.

Years later, when Jorge Mario Bergoglio became Pope Francis, I felt that same opening again—this time from the Vatican itself. A pope who washed the feet of prisoners. A pope who lived in a modest guesthouse instead of the Apostolic Palace. A pope who spoke of mercy more than judgment. He became, to many of us, a gentle echo of Christ’s compassion.

Francis’s Gentle Revolution – beacon of hope

Pope Francis, the first Jesuit to lead the Catholic Church and the first pope from the Americas, brought a quiet revolution to the Vatican. He softened the tone on once-divisive issues—homosexuality, divorce, interfaith relations—without changing doctrine. He preferred gestures to declarations.

In 2013, just months after his election, Francis visited Lampedusa, an Italian island where thousands of migrants had drowned at sea. Standing before a plain wooden cross made of shipwrecks, he asked, “Who has wept for these people?”

He wept.

In 2016, after the bombing in Nice, he met with survivors and their families, urging love instead of vengeance. In Abu Dhabi, he signed the Document on Human Fraternity alongside a leading Sunni cleric—an extraordinary gesture of religious solidarity. In his landmark encyclical Laudato Si’, he made care for the Earth a moral and spiritual mandate, calling climate change a sin against the poor.

“Build bridges, not walls,” he once said. At a time when many leaders chose division, Francis chose the suffering. He will be missed. Read – The last humble Pope.

Choosing the Next Pope

Now, with Pope Francis gone, the Catholic Church stands at a crossroads. Will the next pope carry forward his legacy of humility and compassion—or return to the heavy-footed politics of old Rome?

The answer matters—not just for Catholics, but for anyone watching how power shapes morality. Because the papacy, for all its spiritual significance, is not immune to the darker tides of history.

Popes Who Did Not Preach Peace – despair

Francis may have been a shepherd of kindness, but not all popes have worn the same wool.

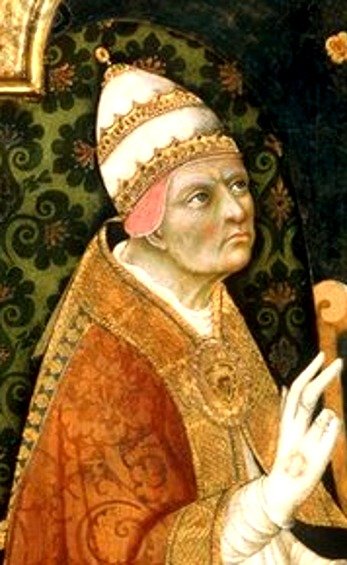

Take Pope Alexander VI—Rodrigo Borgia—whose reign in the late 15th century was a symphony of corruption, nepotism, and scandal. He filled the Vatican with his children and auctioned off church offices like trinkets.

Or Pope Urban VI, whose violent temperament split the Church in two during the Western Schism. So volatile was his rule that many of his own cardinals sought to replace him—sparking decades of ecclesiastical chaos.

Pope Leo X, the Medici pope, once said, “Since God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it.” He emptied the Church’s coffers with lavish feasts and indulgences, paving the road for Martin Luther’s Reformation.

And then there’s Pope Benedict IX, who became pope as a teenager and, according to historians, sold the papacy like a used relic when he lost interest. His reign was so scandalous that Dante placed him in the eighth circle of Hell.

A Hopeful Return?

So, who will take the throne of St. Peter next?

It is tempting to wish for another Francis—someone who will hug lepers, sleep simply, and remind us that the Church’s power should be worn like a linen robe, not an imperial cloak.

But the conclave is rarely about symbols. It is about politics. Culture. Geography. The interplay of old alliances and new fears. And still, many Catholics—and many more outside the Church—hope for a leader who understands that faith is not built in gold-trimmed basilicas but in the quiet service of others.

Whether we get that, only the smoke from the Sistine Chapel will tell

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

If you had to name this article, what would you call it? Being a magazine that is but 1.5 months old, naming articles is a bit of a challenge because we have to work harder to get viewers attention, yet I have boundaries around click bait.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!