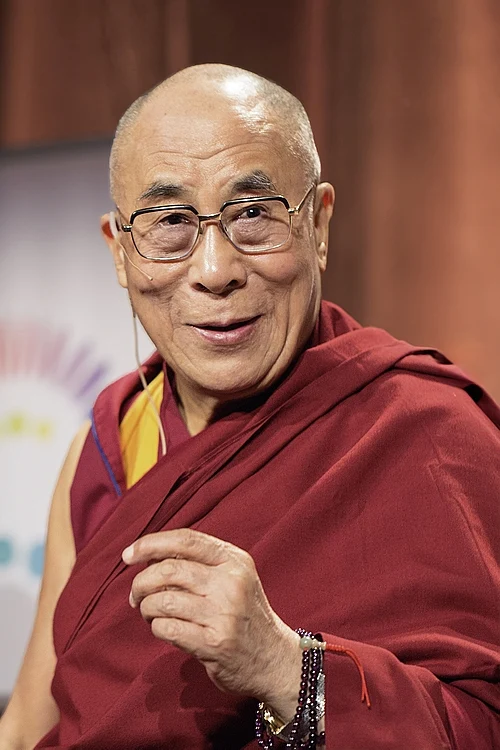

As the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, approaches his 90th birthday, the question of who will carry forward his mantle has become a geopolitical flashpoint, with the next Dalai Lama the 15th reincarnation. Historically, Tibetan Buddhists entrust a small circle of senior lamas—especially the Panchen Lama—with identifying the reincarnation of their spiritual leaders. But Beijing, asserting its sovereignty over “China’s Tibet,” has vowed to install its own successor. Below are two competing narratives shaping the world’s understanding of the Dalai Lama’s and Tibet’s future.

China’s Official Narrative

From Beijing’s perspective, Tibet has been an integral part of China since ancient times, a claim woven into official statements and state education. Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning has asserted that “the lineage of the Dalai Lama, living Buddha, was formed and developed in China’s Tibet, and his religious status and name were also determined by [China’s] central government… We have the legal right and responsibility to approve the reincarnation of living Buddhas.”

Beijing contends that the Qing dynasty’s 1793 Golden Urn lottery system remains the lawful mechanism for selecting Tibetan reincarnations, reviving it as a tool to preempt any “separatist” influence. In 1995, when the Dalai Lama recognized six-year-old Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as the 11th Panchen Lama, Chinese authorities swiftly detained him and installed their appointee, Gyaltsen Norbu. Although Beijing now insists that the “missing Panchen Lama “is being educated, living a normal life, growing up healthily and does not wish to be disturbed,” his family has not been seen in public for thirty years—fueling suspicions of political detention rather than “protective custody.”

More recently, China has moved to codify its control through draft regulations that would require all reincarnations of Tibetan Buddhist leaders to obtain state approval. Beijing argues this safeguards religious traditions from foreign meddling—but critics view it as a frontal assault on Tibetan culture and spiritual autonomy.

The Dalai Lama’s Narrative

For Tenzin Gyatso and his followers in exile, the essence of Tibetan Buddhism transcends borders and bureaucracies. Fleeing Lhasa in 1959 after a failed uprising against Chinese rule, the Dalai Lama established the Tibetan government‑in‑exile in Dharamshala, India, where he has lived ever since. He has repeatedly affirmed that any legitimate successor must emerge “from the free world,” free of political coercion.

In March, he told senior monks that “the successor to the Dalai Lama must be chosen through spiritual signs and the unanimous consent of our tradition—no earthly power can dictate our destiny.” On July 1, he convened eleven of Tibet’s highest lamas at his Indian residence, signalling an imminent announcement about his succession framework. According to officials close to the matter, his forthcoming written statement will likely:

- Delegate authority to the Gaden Phodrang Foundation and the Tibetan parliament‑in‑exile to oversee the search

- Rule out the use of the Golden Urn and any state‑sanctioned lottery

- Emphasize that his reincarnation could appear anywhere, potentially as a girl or even in a new “modern” form of leadership

- Urge Tibetans worldwide to reject any Beijing‑appointed Dalai Lama

Amid these preparations, he offered a glimpse of his outlook: “The rest of my life I will dedicate for the benefit of others, as much as possible… There will be some kind of a framework within which we can talk about the continuation of the institution of the Dalai Lamas.”

A Question for the Future

As both narratives harden, the world watches: will Tibet’s next spiritual leader emerge through age‑old rites guided by the Dalai Lama and his community in exile, or under the watchful eye of Beijing? And what becomes of Tibetan identity if two successors emerge simultaneously? In the decades to come, pilgrimage routes, monasteries, and the very fabric of Tibetan life may hinge on which narrative prevails—and whether faith can outlast politics.